The Cabin John Aqueduct, Cabin John, MD

Article written by C. Scheffey & B. Dennis

The Cabin John Aqueduct (Latitude 38.972779, Longitude -77.148665). [Photography by Bernie Dennis.]Following the completion of the boundary survey for the District of Columbia in 1792, development of the new city moved at a steady pace. As the city grew, relying on individual wells and springs became a source of concern. By 1850, water shortages for both consumption and fire protection were feared. Therefore, the Army Corps of Engineers was directed to conduct studies for an adequate water supply for the Nation's Capital. An officer with the Corps, Montgomery C. Meigs, was placed in charge of the studies.

Meigs' plan included a dam above Great Falls on the Potomac: a nine-foot diameter conduit and tunnel aqueduct 12 miles long, a receiving reservoir at Dalecarlia, a sedimentation reservoir in Georgetown, and a cast iron pipe distribution system. Work began in 1853, with Meigs overseeing both design and construction. The path of the aqueduct would require it to cross Cabin John Creek where Meigs conceived a multi-arch masonry aqueduct bridge.

In May 1855, Meigs hired a 25-year-old assistant engineer, Alfred L. Rives. Rives studied engineering at Virginia Military Academy (VMI) and in Paris. In 1854, he was the first American to graduate from the prestigious École des Ponts et Chaussées (EPC), noted for training the elite French corps of engineers in the mid-nineteenth century. During his studies, Rives became acquainted with the Grosvenor Bridge over the River Dee at Chester, England. Meigs also was familiar with this 200-foot long span bridge through ICE Transactions. An entry in his journal states, “This is the greatest span now standing, in stone. It is 200 feet. I should very much like to build such a one.”

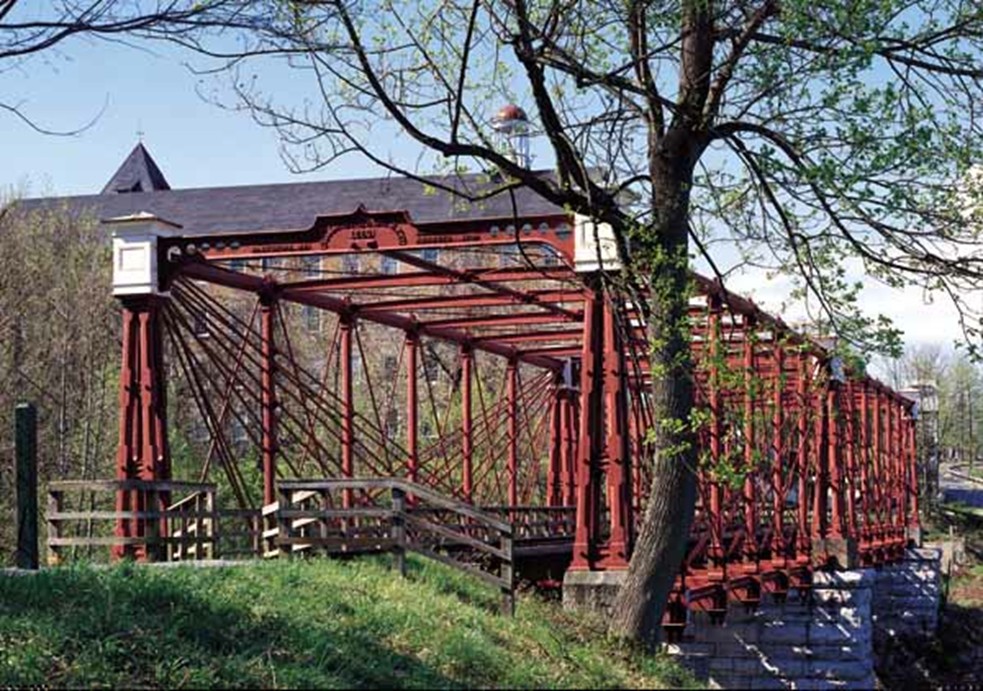

Constructed in 1863, it remains in active use today.Together, Meigs and Rives evolved the aqueduct design for a single 220-foot span arch with a rise of 57.25 feet. Work began in 1857, but suffered interruptions due to lack of funds in 1859 and was eventually suspended in 1861 at the outbreak of the Civil War when Meigs and other military engineers were put to work on the fortifications of Washington. Rives, along with Secretary of War Jefferson Davis and many southern military officers, joined the ranks of the Confederacy. A revealing article on the roles of Meigs and Rives, entitled, “Alfred L. Rives and the Cabin John Bridge: Creating an Unprecedented 67m Masonry Arch at Mid-Nineteenth Century,” by Dario A. Gasparini and David A. Simmons, can be found in the Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History, May 2009.

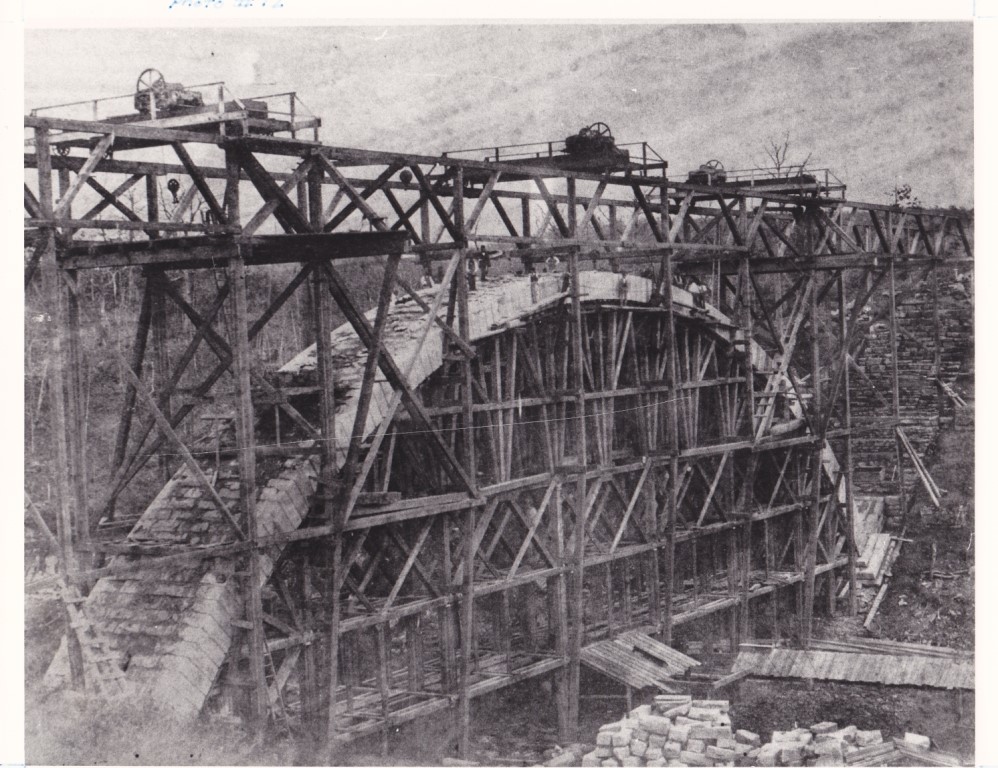

The aqueduct consists of an arch rib of dressed granite. The stones are four feet thick at the crown and six feet thick at the spring points. The spandrel walls are sandstone, backed by brick. The stone was quarried in Maryland at a site upstream on the Potomac. The quarried blocks were transported via the C & O Canal and transferred through a lock into the flooded valley under the aqueduct. Traveling cranes on timber falsework were used to place finished stone blocks. The MacArthur Blvd. roadway and coping were added 40 years later to accommodate traffic.

Following the delay due to the war, work on the structure eventually resumed and was completed in 1863. It began to carry water immediately and has been in use continuously since that time. When completed, it was the longest masonry arch span and held the record for 40 years. The American Society of Civil Engineers named it a "National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark" in 1972. The ASCE plaque shares a pedestal mount with a plaque by the American Water Work Association on the south west end of the MacArthur Blvd. single lane bridge.

The Washington Monument undoubtedly is the most prominent of Washington's engineering landmarks. It had recently been in the news following the August 23, 2011 M5.8 earthquake in Mineral, VA that caused minor damage to the structure.

The Washington Monument undoubtedly is the most prominent of Washington's engineering landmarks. It had recently been in the news following the August 23, 2011 M5.8 earthquake in Mineral, VA that caused minor damage to the structure. The monument is an outstanding example of the art of masonry construction and foundation engineering. It stands 555 feet, 5-1/8 inches tall on a raised terrace. The base of the shaft 55 feet square and the walls 15 feet thick. At its top the shaft is 34 feet square with walls 18 inches thick. The outer face is marble with a granite backing up to the 452-foot level where from that point the walls are marble throughout. It is topped with a 100-ounce aluminum tip lightning-rod

The monument is an outstanding example of the art of masonry construction and foundation engineering. It stands 555 feet, 5-1/8 inches tall on a raised terrace. The base of the shaft 55 feet square and the walls 15 feet thick. At its top the shaft is 34 feet square with walls 18 inches thick. The outer face is marble with a granite backing up to the 452-foot level where from that point the walls are marble throughout. It is topped with a 100-ounce aluminum tip lightning-rod

The monument lies on an east-west axis between the Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial and is currently maintained by the National Park Service. It is still the tallest masonry structure in the world. The American Society of Civil Engineers designated the Washington Monument a "National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark" in 1981. The plaque is located at the top observation deck of the monument on a screen at the top of the stairs descending to the lower level for the elevator.

The monument lies on an east-west axis between the Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial and is currently maintained by the National Park Service. It is still the tallest masonry structure in the world. The American Society of Civil Engineers designated the Washington Monument a "National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark" in 1981. The plaque is located at the top observation deck of the monument on a screen at the top of the stairs descending to the lower level for the elevator.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, settlement along the Potomac River west of the Allegheny Mountains was well under way. In 1749, the Ohio Company was established to develop the growing valley and capitalize on the untapped fur trade with the Indians by utilizing the Potomac as a route to the west.

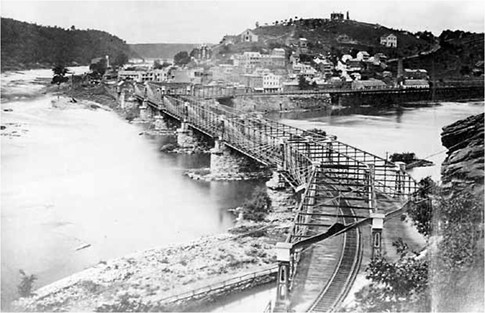

By the middle of the eighteenth century, settlement along the Potomac River west of the Allegheny Mountains was well under way. In 1749, the Ohio Company was established to develop the growing valley and capitalize on the untapped fur trade with the Indians by utilizing the Potomac as a route to the west. The Patowmack Company was formally organized at a meeting of the stockholders on May 17, 1785. Washington was elected its first president, and James Rumsey, the early experimenter with the steamboat, engaged as the chief engineer. The proposed project was to have a series of short by-pass canals to skirt the falls which occurred at several locations along the course of the river. There were to be five altogether at House's Falls, Harper's Ferry, Seneca Falls, Great Falls, and Little Falls.

The Patowmack Company was formally organized at a meeting of the stockholders on May 17, 1785. Washington was elected its first president, and James Rumsey, the early experimenter with the steamboat, engaged as the chief engineer. The proposed project was to have a series of short by-pass canals to skirt the falls which occurred at several locations along the course of the river. There were to be five altogether at House's Falls, Harper's Ferry, Seneca Falls, Great Falls, and Little Falls. The four locks at Little Falls, constructed in 1795, were the first to be completed. Work began on the locks at Great Falls and was not finished until 1802. The system at Great Falls consisted of five locks, each one hundred feet in length and walled with large blocks of hand-hewn sandstone. It was necessary to blast and cut a deep cleft through the solid rock cliff of the Potomac River’s Mather Gorge rising seventy-seven feet from the river level below to the river level above the Falls. The rock blasting was one of the first uses of black powder. The passage through the rock wall had to be large enough to accommodate loaded bateaus: a channel at least twelve feet across. The typical bateau (flat bottom boat) was anywhere between fifty to seventy-five feet long and five feet in width and carried up to 20 tons of cargo. The total lift was seventy-seven feet distributed through the locks with the greatest lift in any one lock of nineteen feet.

The four locks at Little Falls, constructed in 1795, were the first to be completed. Work began on the locks at Great Falls and was not finished until 1802. The system at Great Falls consisted of five locks, each one hundred feet in length and walled with large blocks of hand-hewn sandstone. It was necessary to blast and cut a deep cleft through the solid rock cliff of the Potomac River’s Mather Gorge rising seventy-seven feet from the river level below to the river level above the Falls. The rock blasting was one of the first uses of black powder. The passage through the rock wall had to be large enough to accommodate loaded bateaus: a channel at least twelve feet across. The typical bateau (flat bottom boat) was anywhere between fifty to seventy-five feet long and five feet in width and carried up to 20 tons of cargo. The total lift was seventy-seven feet distributed through the locks with the greatest lift in any one lock of nineteen feet.